H1: Deciphering the 12 Factor Applications Style

“Innovation is the outcome of a habit, not a random act.” — Sukant Ratnakar

Background

When I interact with software developers on campus, there is something enviable about what they do. Once in a while, the thought of transitioning to computer science crosses my mind, but deep in my heart I know I wouldn’t trade a dime for Mechatronics. My experiences in this field are quite memorable. When I heard Kelsey Hightower talking about the 12-factor application paradigm, I was intrigued. I read about it and got the essence of it. The dopamine levels then relaxed. One year later, during the just-concluded JKUAT SES Tech Week, the speakers emphasized building resilient applications.

The 12-factor paradigm is predominantly applied in software development, but could we extend an olive branch to the hardware world? The rise in IoT applications sparked my idea for writing a blog series on the 12-factor IoT paradigm for IoT applications. The recent Facebook outage had a cascading effect on the internet which gave me more reasons for doing this. Are we capable of building resilient applications that scale on their own?

The twelve-factor app is a paradigm of software app development technique that saves time and money for new engineers entering the project. It also uses declarative formats for setup automation, maintains a clean contract with the operating system, and maximizes portability between execution contexts. Without requiring substantial modifications to tooling, architecture, or development methods, it can scale up.

Introduction

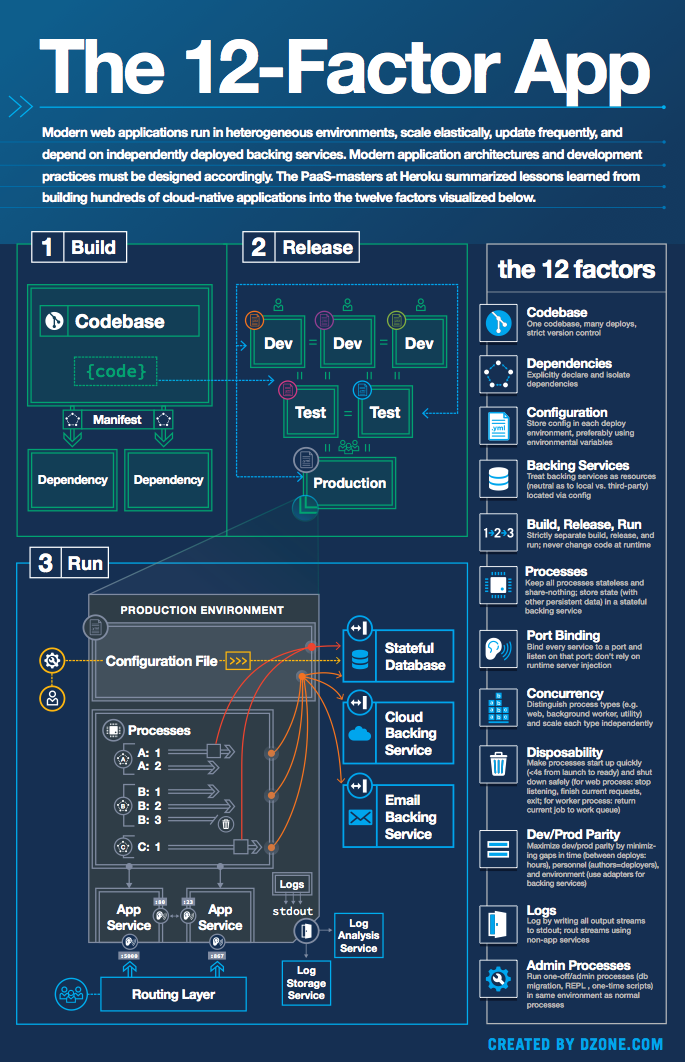

After working on the development, operation, and scaling of hundreds of thousands of apps on the Heroku platform, Heroku developers created the Twelve-Factor App methodology. They found that successful apps have a set of key concepts in common. The Twelve-Factor App, which was first released in 2012, tries to distil that knowledge into 12 factors of best practices.

The Factors

- Codebase

- Dependencies

- Config

- Backing services

- Build, release, run

- Processes

- Port binding

- Concurrency

- Disposability

- Dev/prod parity

- Logs

- Admin processes

This idea has lasted seven years, and people are proposing changes be implemented to make it more relevant for today’s applications. Some have argued that three more additional factors should be included, which are:

- Telemetry

- Security — This is an important argument as the s in IoT usually implies security.

- “API First”-philosophy

In various respects, an IoT app varies from a cloud app. Every device is crucial, whereas, on the cloud, each server can be treated as a disposable device. A device failure in the embedded world is a severe occurrence that requires immediate attention. The properties of the device are also important. Sensors, interfaces, connecting peripherals, and provisioning processes on a device are app-specific and difficult to replicate on a developer’s workstation. Furthermore, it is frequently built on a CPU architecture that differs from that of the developer’s system. A device can be offline or have intermittent connectivity, and the end-user expects it to function normally or gently degrade.

1. Codebase — Your codebase can be tracked by a version control system with many deployments

A version control system, such as Git, Mercurial, or Subversion, is always used to track the IoT app. A code repository, sometimes known as a code repo or simply repo, is a replica of the revision tracking database. The main platform used for hosting the remote repository is GitHub and Gitlab. There are many hosting platforms but we will not get into them. The repo should share root commit to maintaining the state of the files, basics implementation of a decentralized system

Although each app has only one codebase, it will be deployed numerous times. Deploy is a copy of the application that is currently executing. A production location and one or more staging sites are usually included. Production version runs in production while staging is just immediate and usually given to beta testers to test the application before pushing it to production. Another staging version can be used by alpha tests who are inside the company to test on the IoT application being developed. In addition, each developer has a copy of the application running in their local development environment, which qualifies as a deployment.

Twelve-factor apps believe that code ought not to be shared between applications. If you want to share something, you’ll need to develop a library, add it as a dependency, and manage it through a package manager like pip for python.

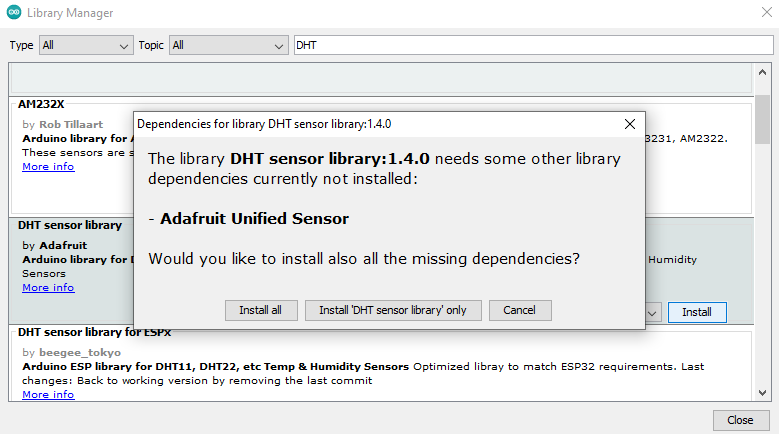

2. Dependencies — Declare and isolate dependencies that the application needs to run

These are key libraries we need for the application to run. Unless you are building the application from scratch, you will need some form of a preexisting library. These libraries will be downloaded as packages. The existence of system-wide packages is never presumed by a twelve-factor app. It uses a dependency declaration manifest to declare all dependencies thoroughly and precisely. During execution, it also utilizes a dependency isolation technique to ensure that no implicit dependencies from the surrounding system “leak in.” Both production and development use the same full and explicit dependency specification.

Twelve-factor apps also don’t depend on the presence of any system tools being assumed. While these tools may be available on many, if not all, systems, there is no guarantee that they will be available on all systems where the app will run in the future, or that the version found on a future system will be the same as the version found on a previous system will be compatible with the app.

Some of the dependencies we can use in developing our IoT applications is the Arduino libraries that help us talk to the sensors on various pins and also push the data to a specific endpoint, be it mqtts, WebSocket or HTTPS.

3. Config — Store config in the environment

The configuration of an app might change between staging, production, developer environments, etc. This includes the following:

- Network configurations such as wifi usernames and passwords

- Database resource handles, RabbitMQ, and other backup services

- External service credentials, such as Vault for passwords

- Values specific to each deployment, such as the deploy’s canonical hostname

Config is sometimes stored in the code as constants in apps. This is a violation of the twelve-factor principle, which requires that configuration and code be kept separate. The configuration varies greatly between deployments, while the code does not.

These config files help us show how this application will run.

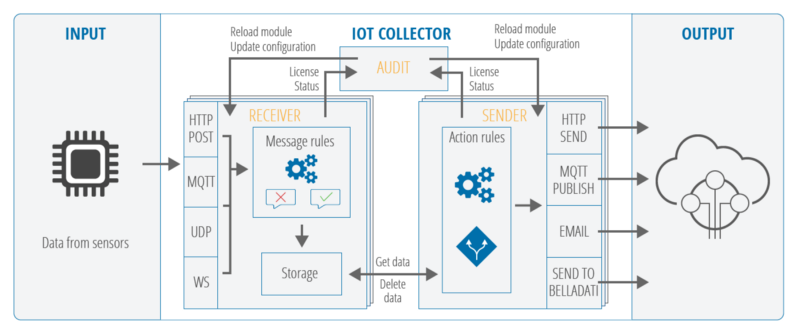

4. Backing services — Backing services are treated as attached resources

The execution environment treats all backup services as attached resources that can be attached and detached. External services, such as databases, external storage, and message queues might be considered resources. They can be accessible by web addresses/URLs or other similar queries, which are set in the configuration. In this manner, the service’s source code can be changed without affecting the app’s core code. The external services should ensure they have high availability and you should have redundancies for your application not to fail.

We can use our external server where we have our MQTT server being hosted and also our databases to store the data. This is a very good example to show how the backing services can be attached as backend services that help us process our data from our IoT device. The execution environment treats all backup services as attached resources that can be attached and detached. External services, such as databases, external storage, and message queues might be considered resources. They can be accessible by web addresses/URLs or other similar queries, which are set in the configuration. In this manner, the service’s source code can be changed without affecting the app’s core code. The external services should ensure they have high availability and you should have redundancies for your application not to fail.

We can use our external server where we have our MQTT server being hosted and also our databases to store the data. This is a very good example to show how the backing services can be attached as backend services that help us process our data from our IoT device

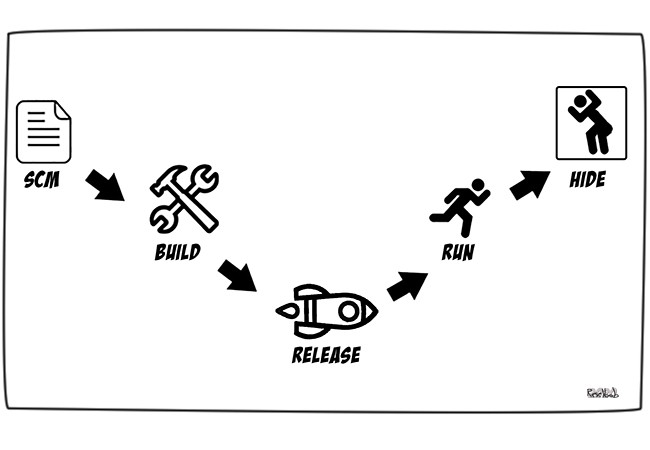

5. Build, release, run — Build and run stages should be independent

Let us understand each stage in more detail.

- Build stage: transform the code into an executable build package. This happens when you compile your code on your machine and produce an executable file.

- Release stage: get the build package from the build stage and combines it with the configurations of the deployment environment and make your application ready to run. The release stage happens in your git hosting services as you will be able to push different versions of the application creating different releases.

- Run stage: It is like running your app in the execution environment. For IoT on steroids, we can use Over The Air updates. This will send updates to the IoT device automatically

You can use CI/CD tools to automate the builds and deployment process. Docker images make it easy to separate the build, release, and run stages more efficiently.

6. Processes — The application is run as one application or more stateless

Applications should be deployed as a single or several stateless processes with persisted data stored on a backend service, such as a database. When you can plug data from the MQTT server into the database you will be able to ensure persistent data storage.

This factor’s main principle is that the process is stateless and doesn’t share anything. While many online systems rely on “sticky sessions,” holding data in the session and expecting the next request to originate from the same service is incompatible with this strategy.

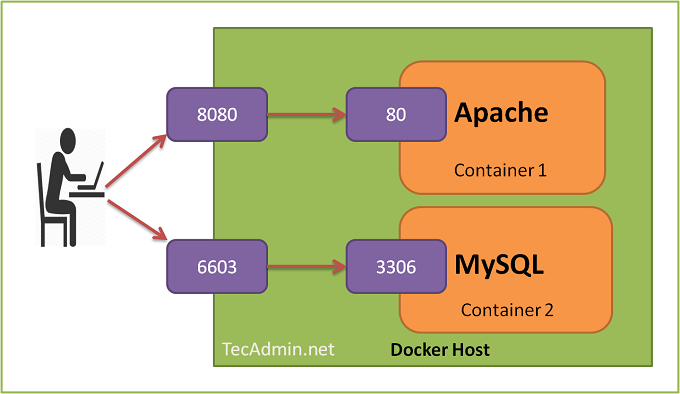

7. Port binding — Export services via port binding

This factor refers to an application binding itself to a particular port and responding to all the requests from that port. The port is declared as part of the configuration variable and provided during execution.

Applications built based on principle do not depend on a web server. The application is self-contained and runs standalone. The backend server services are bundled with the application.

For instance, we will expose our MQTT server through port 1883. This port will be accessible to all authorised IoT devices. Whenever we are doing a system upgrade, the port will remain constant, and as the system is up, we will be able to push data through the port.

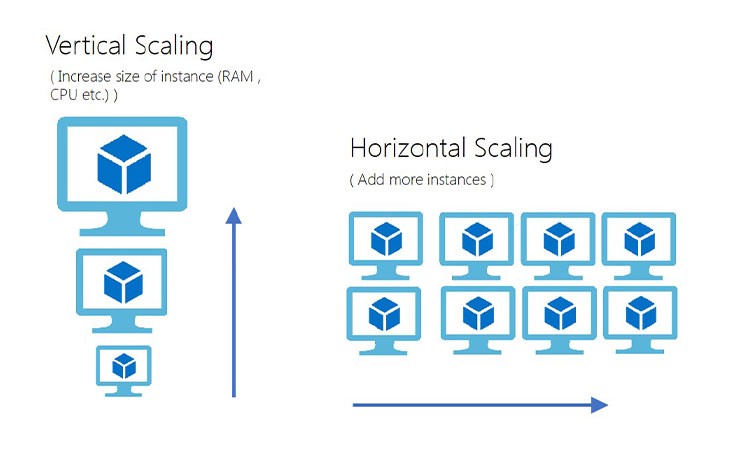

8. Concurrency — Scale out via the process model

We must be able to scale our application services. Twelve-factor app principles suggest considering running your application as multiple processes/instances instead of running in one large system. You can still opt-in for threads to improve the concurrent handling of the requests.

In a nutshell, twelve-factor app principles advocate opt-in for horizontal scaling instead of vertical scaling.

- vertical scaling- Add additional hardware to the system

- Horizontal scaling — Add additional instances of the application

By adopting containerization, applications can be scaled horizontally as per the demands.

9. Disposability — Maximize robustness with fast startup and graceful shutdown

Fast startup and gentle shutdown increase robustness. The processes in the twelve-factor app are disposable, which means they may be started or terminated at any time. This enables rapid elastic scalability, rapid deployment of code or configuration updates, and production deployment resilience. Startup time should be kept to a minimum in all processes. Only a few seconds elapse from issuing a command until the process is up and ready to handle requests or jobs. Short startup times provide the release process and scaling up greater agility; they also help with robustness since the process manager can more easily relocate processes to new physical machines as necessary.

When the process management sends a SIGTERM signal, the processes gracefully exit. Graceful shutdown for an MQTT process is accomplished by stopping listening on the service port (therefore denying any new requests), allowing any current requests to be complete, and then leaving. HTTP queries are short (no more than a few seconds) under this paradigm, and in the case of long polling, the client should seek to rejoin smoothly when the connection is broken.

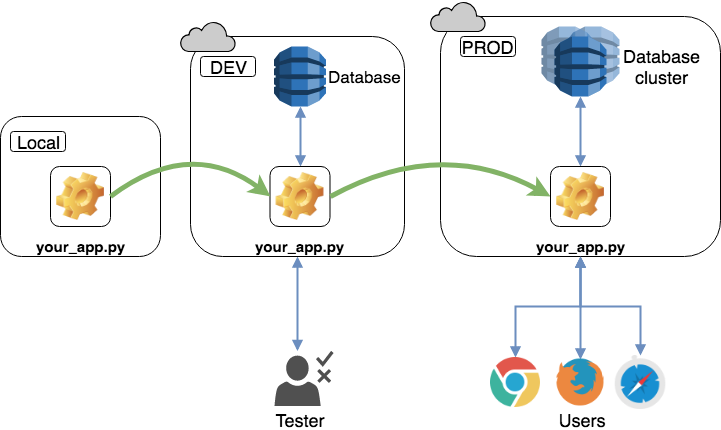

10. Dev/prod parity — Maintain consistency between development, staging, and production environments

According to the twelve-factor article, the difference between the development and production environments should be kept to a minimum, which reduces the chances of bugs appearing in a given environment.

To keep variations between development and production minimal, teams collaborating on a project should use the same operating systems, backup services, and dependencies. Continuous deployment requires less time as a result.

When developers minimize the number of variations between the development and production stages, the continuous deployment process becomes smoother.

11. Logs — Treat logs as event streams

When troubleshooting production problems or understanding user behaviour, logs become extremely important. Logs provide visibility into a running application’s behaviour.

A 12-factor app should not concern itself with routing or storage of its output stream. All log files should be written to the standard output stream (stdout), and the environment decides how to process this stream. This might be as easy as sending to a terminal or as complex as storing and forwarding to a log indexing and analysis system.

12. Admin processes — Execute administrative and management activities as one-time processes.

According to this factor, any admin processes should run in the same environment as the app’s regular long-running processes. To perform one-time admin tasks in a local deployment, developers use a straight shell command inside the application checkout directory. Developers can utilise ssh or a similar remote command execution method offered by the deployment’s execution environment to run such a process in a production deployment.

If you liked this article, click the👏 multiple times below so other people will see it here on Medium.

Let’s be friends on Twitter. Happy Coding 😉

Acknowledgements

References

1. https://dzone.com/articles/12-factor-app-principles-and-cloud-native-microser-1

2. https://simpleprogrammer.com/twelve-factor-app/

3. https://hackernoon.com/the-twelve-factor-app-12-best-practices-for-microservices-sf2vz31wn

4. https://mobycast.fm/episode/are-you-well-architected-the-twelve-factor-app-framework/

5. https://developers.redhat.com/blog/2017/06/22/12-factors-to-cloud-success

6. https://12factor.net/disposability

7. https://scand.com/company/blog/the-twelve-factor-app-methodology/

8. https://github.com/adamwiggins/12factor/blob/master/content/dev-prod-parity.md